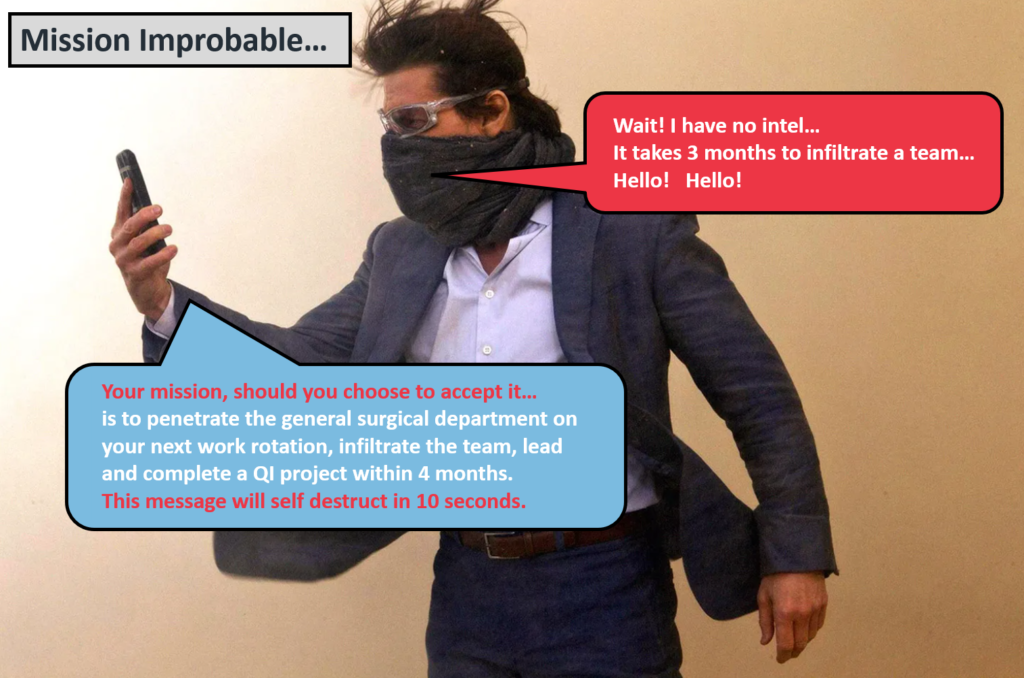

An experience of an F2 doctor trying to do QI in 4 months…

This might seem a bit familiar when you are starting out as the new doc on the block in a busy hospital department. You are daunted by the prospect of learning the clinical ropes. You know you need to get on with a quality improvement project, because your curriculum says so. But… you hardly know anyone or how things work around here.

Your consultant supervisor smiles innocently and asks what QI project you would like to do. You smile back and say something remotely intelligent, knowing you just lifted this off the departmental induction pack 5 minutes ago. Really you were hoping that the consultant would come out with the improvement project ideas. Surely they would be more aware of what the problems are in their department, right? But no, it is down to you.

So off you go, wondering what improvement work is out there. Asking random people, hoping someone will help you on your quest to do improvement work. That one-hour QI intro lecture at the beginning of the year seems a distant memory.

In the first month, most of your time is spent trying to keep your head above water. You often feel overwhelmed. There is just so much to know and learn. Trying to start a QI project seems less of a priority when compared to the clinical work pressure. You want to be safe for your patients… You will think about QI later. A form of ‘duality’ occurs in your mind. The need to separate the clinical work to that of the improvement work. Yes, to compartmentalise will help you cope and get through the day. You will leave the ‘QI bit’ to Thursday afternoon when the staffing is better and it is quieter.

You become more aware that you are a now a small cog in a team you are not familiar with. Some staff have been there for years, some have just started, just like you. A few weeks pass, you are getting to know all the players; who is important in the team, who can help and who to avoid. But as a relatively new doctor, you don’t feel safe proposing any improvement ideas to the team. How will they react to your idea? Will you end up looking foolish amongst your peers? Can you speak up to your consultant surgeon with many years experience and say there might be a problem worth fixing? Do they even care what you think? Do you feel psychologically safe enough to bring this up??

The 4-month rotation mercilessly moves on. A few on-call weekends pass. It is already week six. Not much has happened on the QI front. Some ideas form, but nothing concrete. So much for the flying start… a few more weeks pass. You begin to feel more comfortable within the department, you know your role within the team. Importantly, you are now developing relationships with your ward nurses, physios and pharmacists. One or two are now your friends.

A few more weeks pass. The clinical work pressures remain, but you are performing well clinically, you have formed an identity and feel valued for your work. You begin to revisit your need to complete a QI project. This is your last rotation for the year, your ARCP assessment is just around the corner. You wanted to make a meaningful impact on patient care through QI, but now there is not enough time. Perhaps you should focus on something that is more manageable? Try to keep the improvement small, the change ideas simple. Maybe focus on some ‘low-hanging fruit’ QI. Possibly a stool chart PDSA, or perhaps a handover sheet for the morning surgical meeting. You could print the sheets out yourself. No need to get the wider team involved. The QI might not sustain after you leave, but at least it is something you can show at ARCP. You will try and do a ‘proper’ QI next year.

The 4-month rotation is now up. The QI project done. A couple of PDSA cycles mashed together. The time-sensitive ticking clock of QI negated, just in time for ARCP. But the QI ticking clock has now been replaced by another type of ‘tick’. The all too familiar QI tick box

The above story is fictional. It is based on the findings of a qualitative MSc study exploring how the social learning environment influence how trainee doctors engage with improvement work (Choudhury 2022). F2 doctors, educational supervisors and trust improvement specialists were interviewed.

We can explore the challenges that F2 doctors face immersing themselves within a new clinical department through the lens of Tuckman’s team building model (Tuckman 1965). The model described a number of stages for team development.

Forming – a new team is formed with rotational doctors joining every 4 months. Tasks and roles are not always defined.

Storming – Individual boundaries become contested and conflicts can occur. There is often jostling for position for new staff.

Norming – Members of the team resolve their differences, with greater acknowledgement of other team members strengths and weaknesses

Performing – The team becomes functional, works effectively and efficiently to complete tasks. There is high development of roles and responsibilities

Adjourning – This phase does not always occur. Especially for junior doctors, as they are often not there long enough. Can lead to missed opportunities to celebrate successes or even mourn their departure.

The illustration below highlights the strain for F2 doctors when faced with the competing priorities of performing clinical duties and improvement work all at once during a four-month placement.

So what does this all mean?

These F2 doctors describe an uncomfortable feeling of a clock ticking down with growing pressure to complete a piece of improvement work within a four month window. This is challenging for an established member of a departmental team, but near impossible for new members such as F2 doctors.

So why the mad rush to finish the QI project in 4 months? We know that complex problems can often take many years to improve often under the umbrella of continuous improvement. A more systematic sustainable approach to improving quality of care, with no obvious start or end date to the improvement programme.

Could there be extrinsic drivers to explain this behaviour? F2 doctors can describe in detail the scoring systems for QI and clinical audit with their relative weighting for shortlisting. Just as an example, the specialist interview shortlisting for physician higher training for QI attainment suggests to score the top prize of 5 shortlisting points, you need cover:

“all aspects of two [PDSA] cycles where you can demonstrate a leadership capacity by supervising other members of the team.”

Wow… that would be an impressive feat considering it takes three months to get your feet under the door in a new department! Did I mention, the F2 doctor will also need to lead and inspire these departmental old-timers in a QI programme… I hope they had all their leadership experience front-loaded in medical school.

Training curricula for doctors can also be overly prescriptive in what constitutes ‘exemplary standard’ of QIP. Let us take the example from physician core training assessment tool for QI.

“QIP topic related to an important clinical problem, detailed and exhaustive methodology applied, appropriate presentation of results with correct interpretation and comprehensive conclusions. Plans for future direction of QIP highlighted. An exemplary QIP.”

All of the above in 6-months for internal medical trainees, a lot to do and not a mention of a team approach to QI anywhere…

So have we set-up our new doctors to fail? To achieve the unachievable? Have they signed up to Mission Improbable? The educational and competitive career progression mandate has led to trainees seeing QI as a hurdle to overcome and not seeing improvement for what it should be, an opportunity to improve the patient experience. It is in fact us who have led them to the ‘QI tick box’. That short term unsustainable ‘low hanging fruit’ piece of QI work done in haste, that has little impact on patient outcomes.

So what could we do differently?

Certainly there is recognition for change. It was encouraging to see the recent publication from the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and their take on assessment of QI published in 2023. The document states trainees are not required to have done entire projects from start to finish (phew!), and there was no need to lead a project at any stage of training (double phew!).

This change in direction can be a catalyst for major quality improvement reform for doctors in training. It is badly needed. NHS organisations need our rotational trainee doctors to support the often complex challenges facing many trusts. They are the ones seeing the problems daily, why should they not be part of the response?

We can help our trainee doctors by:

Promoting at trainee induction the correct mindset for improvement, specifically, that meaningful QI participation in results in better patient experience

Identify departmental improvement work early in their four-month rotation. They should not be searching for it

Allow trainees to remain on improvement programmes for greater than four months when feasible, if not possible, ensure mechanisms for handover of their QI work

Create multi-disciplinary coaching and support groups for rapid onboarding of new doctors through a departmental QI Faculty

NHS trust corporate teams could ensure local departmental improvement work is recognised and appropriately supported rather, rather than focus solely on executive driven large scale programmes

Great read. Thank you.